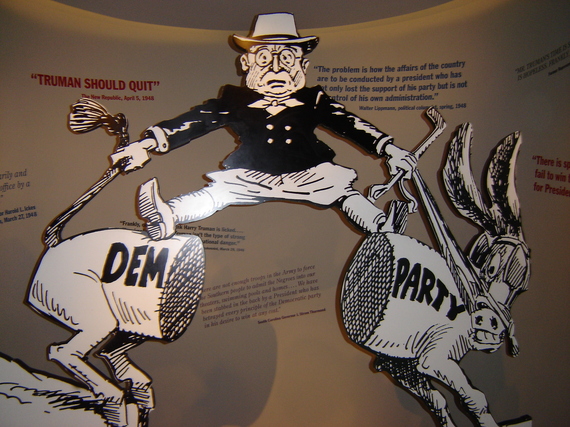

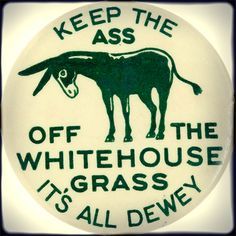

On paper, it looked like Thomas E. Dewey was a shoo-in to win the 1948 election and return the Presidency to his Republican Party after 16 years of Democratic Party rule. He had come within two million votes of beating Franklin Roosevelt in 1944. Four years later it was not the iconic FDR he'd be facing or the wartime unity that he commanded, but Harry Truman, who was mired in misery at home and abroad. The Dixiecrats had splintered off in protest of Truman's bold civil rights program, while former VP Henry Wallace led the Progressives leftward with conciliatory foreign policy and plans to nationalize American industry.

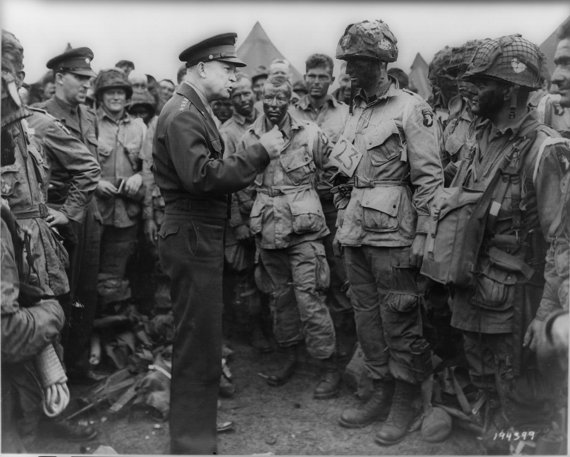

Then there was the aftermath of postwar strikes that claimed millions of work days in 1946 and 1947 and isolated Truman from the unions after he took a hard line stance. The President almost didn't make it onto the ticket at all - the increasingly influential Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) and several big name Democrats wanted Dwight Eisenhower instead, a push only halted by Ike's refusal to run. And abroad Communism was on the march in China, and pushed Truman to the brink when the Soviets cut off West Berlin from food, medical supplies and coal with the Berlin Blockade. No wonder polls put Dewey up to 20 points ahead of the incumbent and almost three quarters of newspaper editors in a September 1948 survey backed the former New York Governor to take down Truman come election night.

And yet, somehow, Dewey lost the 1948 election and Truman claimed one the most unlikely victories in US history. So just how did the Man from Missouri pull it off? Well, there are a variety of factors, not least carefully targeted campaigning to black voters, farmers and blue collar workers, not to mention Truman's Herculean Whistle Stop Tour, which saw him give up to 16 speeches a day as he traveled 31,000 miles across the nation.

But a less obvious factor in Truman's win and Dewey's demise was the DNC Research Division. Holed up in small, airless offices above a building site in Washington's Dupont Circle, seven men beavered away day and night creating "Files of the Facts" - extensive dossiers on housing, civil rights, education and the other main planks of the Democratic platform. They then sent these to Truman's campaign team, who distilled them into bullet points for the President to review.

The real advantage that the seven journalists, city planners and policy experts provided wasn't macro level overviews, however, but localized details that any modern political "War Room" team would be proud of digging up. Using Works Progress Administration guides and local newspapers from across the country, the Research Division compiled talking points for each of the 352 places Truman spoke in on his June 'inspection tour' out West and the main Whistle Stop Tour in the autumn. As they were such a small group, the staffers were only ever working 48 hours ahead of Truman's train, which received new information when a runner went to the closet municipal airport to get new packets.

The specifics covered all the main election topics. Those who gathered in LA's Gilmore Stadium on September 23 found out that in 1940 only 5 percent of LA homes sold for more than $10,000, while eight years later, that figure had increased to 50 percent - evidence Truman used to call for inflation controls. A Winona, Minnesota audience that listened to the President on October 14 learned that, "Back in the Republican depression year of 1932, Minnesota farmers made less than quarter of a billion dollars. Last year, the income of Minnesota's farmers was a billion and a half dollars."

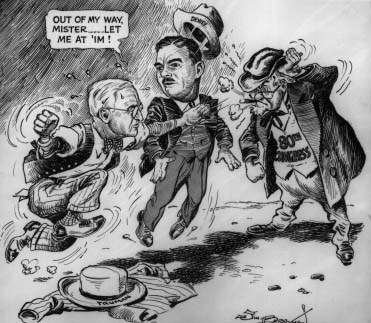

As well as feeding the President nitty gritty details, DNC Research Division head Bill Batt and his staff critiqued Truman's talks and provided suggestions for improvement. And it was Batt who pushed Truman's aide Clark Clifford to bend the President's ear on calling the "do-nothing" Congress back for a special summertime "Turnip Day" session in his Democratic Convention speech. And that's just what Truman did. The Congressman, spurred by Republican Robert Taft's assertion that "We're not going to give that fellow anything" passed no meaningful laws during this time, giving Truman even more ammunition for his accusation that the Republican-controlled legislative body was failing the country.

Click here to finish reading this article via Huffington Post UK.

Learn more about the role of the Research Division in my new book, Whistle Stop: How 31,000 Miles of Train Travel, 352 Speeches, and a Little Midwest Gumption Saved the Presidency of Harry Truman.

If you'd like to purchase a signed copy of Whistle Stop and/or my previous book, Our Supreme Task: How Winston Churchill's Iron Curtain Speech Defined the Cold War Alliance, please leave a comment below.